by Sam Berman-Cooper

We’ve all been in this situation. 7pm. Paper due tomorrow at noon. No draft. No outline. No time machine. What do you do, what do you do?

Have no fear! Here are a few Quick Tips you can follow to avert disaster.

1. Ask yourself: Have I done the reading? If your answer is “no” go on to step 2. If you answer is “yes,” ask yourself “what are 4 or 5 interesting facts about the reading? If you cannot produce said facts, you answered incorrectly. You may have “done” the reading, but in practice, you may as well have not. Go on to step 2. If you are confident in your mastery of the necessary reading, ask yourself “do I have a good idea to write about?” If your answer is “no,” go to step 3. If your answer is “yes,” go on to step 4.

2. Accept the fact that you are not going to hand in your paper on time. Accept that this is not the end of the world. Email your TF (or whoever is grading your paper) and tell him/her that your paper will be late and you have no valid excuse. Without notification, he/she will be confused as to where your paper is, and probably more irritated than if you had been upfront about it. Go on to step 3.

3. Go over your readings with a pen or a highlighter. Figuring out an idea to write about should be your first priority as you read. Take your time and think carefully about the authors’ arguments. There is no such thing as a good paper without a good idea. Once you’ve decided what you want to argue, go on to step 4.

4. To quote the immortal Douglas Adams: Don’t Panic. You’ve done the readings and you have an idea. It may be that you can still get a good grade. Even if you can’t, just think how many assignments you are going to do here in four years. One average grade won’t kill you (or your chances of making mad bank).

5. DO NOT plagiarize. Let me repeat that. DO NOT even consider plagiarizing. You will get caught. You will get Ad-Boarded. It will go on your record. You will regret it.

6. Figure out exactly how much time you have between NOW and the time your paper is due. Do not try to work straight through. You will get less and less efficient (and worse and worse at writing) if you refuse to take breaks.

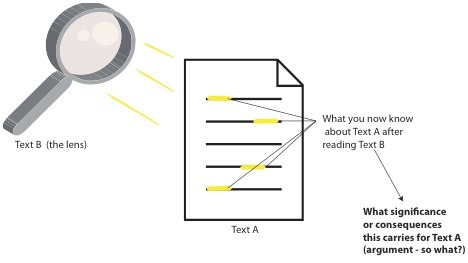

7. Figure out what kind of essay you are writing (lens essay, research paper, etc.) and Check THE WRITING CENTER BLOG for templates. For example, check out Emily’s post for tips on how to write a good lens essay.

8. Quickly create a schedule to accommodate your personal writing process. I like to make very detailed outlines and spend less time drafting and revising. If I have 12 hours to do a close-reading paper (critical analysis of one source or one author), my schedule might look like this:

a. Midnight-1:00am: Use a Writing Center Blog Post to help create a very loose outline – just a vague thesis, ideas for topic sentences, 3- 5 body paragraphs, and possibly a conclusion.

b. 1:00-2:30am: Close-read/re-read relevant parts of the text to find quotes/evidence and flesh out each body paragraph. Add each quote (with its page number/source) to the outline.

c. 2:30-3:00am: Take a break. Get some food, maybe do some jumping jacks. In the short term, 15-20 minutes of exercise is proven to be more effective for waking you up than a 15-20 minute powernap.

d. 3:00-3:45am: Write a thesis statement and introduction. This is the most important part of your essay, so take your time.

e. 3:45-7:00am: SLEEP!!! I cannot stress this part enough. You will have a much clearer mind and work much better and much faster if you get some sleep cycles in.

Check out this page on typical sleep cycles to help you plan your nap. Deep Sleep and REM sleep are particularly important for processing information and feeling alert and energetic when you wake up. If you set your alarm to go off during DEEP SLEEP (stages 3+4) you will probably feel groggy (and not much better at writing) when you wake up. Try to get a least one full cycle (3 hours) and time your naps to not wake up during periods of Deep Sleep.

f. 7:00-7:30am: Shower/eat. Showering will help you wake up, plus it will give you time to think about what you want to say. Don’t go without food. Your mind is a machine, and it needs fuel!

g. 7:30-10:00am: Write your body paragraphs. Follow your outline as closely as possible. This is GO TIME, when the heart of your essay comes to life. You should feel a little pressure at this point, but that’s a good thing – it will make you work faster. As long as your outline includes all the evidence you need, the real work is done. Now you’re just translating bullet points into sentences.

h. 10:00-10:15am: Another break. Stop thinking for a little while. You will feel better.

i. 10:15-11:00am: Write a conclusion and start re-reading/revising. Keep your eyes out for sentences that seem unclear, points that need a little more evidence, spelling and grammar; any problem that can be solved with a quick fix.

j. 11:00-Noon: Final revision. Double-check all your sources and look for carelessly placed words and grammatical errors. Save, print, staple. You have successfully completed an essay in 12 hours. After class, pass out for as long as possible!